A relatively new graduate, concerned that she was starting to experience hand pain after less than two years in practice, recently approached me to ask “Is this normal?” The short answer is, “No.”

She thought the discomfort could be related to strengthening hand muscles. Any dental hygiene instrumentation book will tell you that muscles need to be developed and maintained in order to have the strength for instrumentation. When I dug deeper with this clinician, however, I suspected that the pain she was experiencing could be related to several possible factors. When we talked further, she shared with me she realized that with the demands of her job in private practice, she was more focused on getting the job done and let some of the “rules” she learned in school slide. This will surely make a difference.

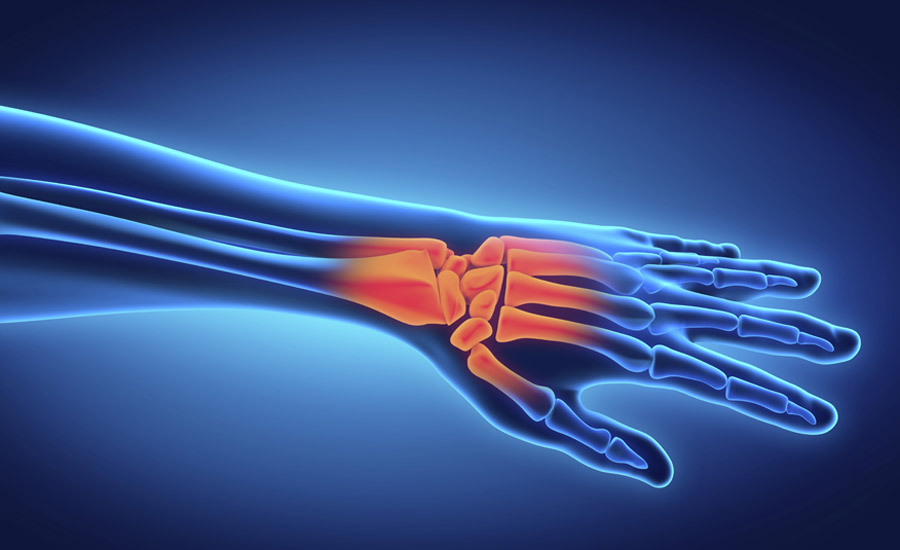

Hand pain can be related to a number of conditions such as tendonitis, arthritis, cysts, carpal tunnel—the list goes on. Evaluation and diagnosis of pain symptoms is important, as the earlier the issues can be addressed, the better the outcome in most cases. Although some conditions can be structural or genetic, the nature of clinical practice is also a precipitating factor. One of the best way to lower the odds of developing one of these debilitating and potentially career-limiting conditions relies largely in part to the message we deliver to our patients: prevention is key.

The purpose of this article is to give you a few pointers and reminders to help protect your hands from potential injury. They are the most important instruments of your profession.

Properly fitting gloves

According to Jill S. Nield-Gehrig, in her textbook Fundamentals of Periodontal Instrumentation, “Glove induced injury is a type of musculoskeletal disorder that is caused by improperly fitting gloves. Symptoms include numbness, tingling or pain in the wrist, hand, and/or fingers.” (1) Gloves that are too tight will pull across the palm and wrist, and will constrict movement. This will lead to muscle strain. Be sure your gloves are loose across the palm and at the base of the thumb. You should be able to close your hand with no constriction. There should be enough room at the wrist to fit your index finger of your opposite hand.

Also bear in mind that gloves that are too loose can also pose an issue in that the extra material will make it difficult to control the instrument, increasing the risk of injury to both the patient and the operator. Too much excess room at the wrist also increases the risk of contaminated material and other potentially infectious matter getting inside the glove.

Grasp

The clinician I referenced admitted to me that she stopped focusing on her grasp once her instructors were no longer watching. She didn’t realize the importance until I could guess how she was holding her instruments based on where she was feeling pain. Her grasp was too tight, and the tip of her thumb was flexed outward.

Remember your modified pen grasp. The pads of your index finger and thumb should be at the same level on the handle and make a soft “C” shape, with space between the two to allow for adequate rolling of the instrument. The side of the pad of the middle finger should be extended and rested lightly on the shank. The ring finger should be straight and act as a stable fulcrum, and the middle finger may be partly stacked on top of it. The pinky should be neutral (neither bent nor flexed). It is important that the grasp stay together without the fingers splitting. I recommend to my students that they get the grasp situated outside the mouth before instrumentation.

The wrist should be neutral; the hand should be in the same plane as the forearm. The hand, wrist, and lower arm function together as a unit, similar to the motion one would make if turning a doorknob. Be sure that you are not holding on to the instrument too tightly. Remember that for exploratory strokes you only need a feather-light grasp. Without it, you will not have good tactility and your hands will begin to hurt. For plaque removal, it's slightly more moderate pressure. With calculus removal, you need to increase the lateral pressure. The leading third of the instrument working end should be pressed firmly to the tooth, with a short pull stroke powered from the wrist, not your fingers. Between each removal stroke, relax your hand. It is also beneficial to use a combination of power and hand scaling.

Sharp instruments

It is important to keep instruments sharp and to sharpen them properly. Without sharp cutting edges, a lot more pressure is needed for successful removal. Dull instruments or those that have been sharpened incorrectly are also much harder to control. This results in hand fatigue, discomfort for the patient, and potential for injury to both parties.

If you are not confident with your sharpening skills, there are tutorial videos online as well as devices that can assist with in-office sharpening. Another alternative is to send instruments out to a reputable sharpening service.

How often you should sharpen is dependent upon many factors such as the number of kits you have, the volume of patients you see, the difficulty level of those patients, etc. According to Neild-Gehrig, one should sharpen at the first sign of dullness. (2) When you feel you need to use more pressure for successful removal or you can no longer feel the bite of a sharp cutting edge on a test stick, it is time to sharpen. Another evaluation technique is to observe the cutting edge held under the light. A dull cutting edge will reflect the light back, where a sharp edge will not.

Exercises and stretches

As an experienced clinician who developed wrist and hand pain from tendonitis after 15 years in practice, I learned from my physical therapist that I should have been stretching and exercising my hands daily. He recommended that I do a customized short series of exercises as frequently as in between each patient. Not all exercises are recommended for all practitioners, particularly if you are already experiencing any discomfort. Always seek the advice of a professional to determine what is best for your particular situation and to avoid injury.

We all know that the practice of dental hygiene comes with increased risks of work-related injuries. The work we do comes with periods of prolonged static posture, and repetitive, precise motions. It is up to us to take all precautions to maintain our health and the longevity of our careers. Prevention is the best strategy. With that, remember the basics when it comes to protecting your assets—your hands.