The idea of bonding restorations into teeth has been around since at least the 1940s with silicate cements and the late 1950s with the adhesion of polymers to tooth structures facilitated by acid etching in the work of Dr. Buonocore.

This etching process has been one of the most controversial and debated topics in dentistry. Various efforts have been directed at creating surfaces that contemporary monomers can penetrate into and harden in place: from selective etching of enamel only, to etching of dentin with low, 10-percent concentrations of phosphoric acid, to complete etching (total-etch) of all tooth structures involved with 35 percent phosphoric acid and finally to self-etch systems.

Polymer durability and etched tooth structure (hybrid layer) should be of primary interest, so both the patient and clinician will be satisfied that the value is worth the effort.

Sensitivity and early failure of adhesive/composite systems has been exhaustively discussed, and still to this day is not agreed upon by many experts. Much of the time, we are left with so little understanding as to why a system failed that we readily place blame on the product, not recognizing how our techniques may have contributed to the process.

Without understanding the inherent strength of the tooth substrate, we are left with guesses and assumptions about how much bond strength is necessary. It seems appropriate to provide a short explanation on how we test the strength of dentin, as this information will serve us well for all future discussions about bonding.

How strong is strong enough?

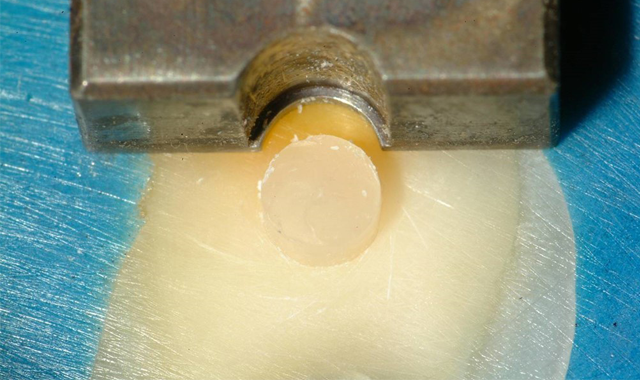

In a method used in a 1999 IADR research project, whole human teeth were embedded in PPMA cylinders and then cut on a lathe to produce a 2.38 mm diameter button of dentin protruding out from the buccal surface (Fig. 1). Buttons were produced in shallow, middle and deep dentin.

The specimens were then loaded into an Instron Universal Testing machine, and a precisely-fitted notched chisel exactly matching the diameter of the button was used to shear the button off. The force used to fracture the buttons ranged from 70 to 100 pounds.

Shallow and middle dentin performed similarly, but the deep dentin became thin as it neared the pulp chamber and broke at lower values — not because dentin is weaker at the deep layers, but because it was too thin and flexed during the test.

When we use a button diameter of 2.38 mm (about the diameter of the shank of a low-speed drill or polishing wheel) one pound equals 1 MPa. It stands to reason that if the tooth takes between 70 and 100 MPa to break, then we would want a composite bonded in place of the dentin to be able to withstand similar loads.

In order to accomplish this test, a notch shape that precisely fits the button must be used to load the specimen .

Interestingly, most of the shear research performed in the past has been performed using a straight chisel, which applies a point-load and falsely implies a lower value than what is actually present if tested correctly.

As of this writing, there are no “all-in-one” adhesives that bond anywhere close to the original strength of dentin. Only a few adhesives today produce values between 60 and 70 MPa .

Many readers may be seeing information like this for the first time and feel that this is absurd. Some may contend that we just do not need that kind of strength to do the job, while others may even claim that it is “too strong.” The view I have taken as a clinician and researcher for the last 25 years is that if nature made a tooth this strong, we must strive to replicate that strength in order to restore true function for normal wear and tear in the oral environment.

This goal has served us well, and we regularly enjoy success in even the most demanding of restorations.

Sensitivity issues

On the topic of sensitivity, we have observed a number of key factors that should be understood about quality bonding, which address these issues directly. Since the work of Dr. Brannstrom in 1981 as well as many other researchers after, we have developed a strong understanding of the reasons for dentin hypersensitivity. We know that fluid movement in the dentinal tubules will press on and irritate the nerve fibers in the tooth.

Direct observation of closing the tubules with resins or monomer systems has proven invaluable in addressing this important issue. The use of cavity varnishes under amalgams, and now the use of desensitizers, is in direct response to this understanding and has provided a valuable tool in this battle.

Of course, with total-etch processes, we now open the tubules directly and see a huge increase in post-operative sensitivity. This all makes sense because earlier generations of adhesive were not hydrophilic enough to actively penetrate all the open tubules and seal the wound we had made in the preparation process.

We know that desensitizers work because the low-viscosity, hydrophilic HEMA easily penetrates the open spaces and, voilà, less sensitivity. But what about an adhesive’s ability to do the same job? Happily, we can say that almost every adhesive, if used properly, can accomplish this task.

It’s all in the technique

Frequently, we find two offices using the same product on two different patients with one suffering rampant sensitivity while the other has little or no complaints of this nature. So, just what makes the difference? Technique, technique, technique!

Once a clinician understands that bonding is an infusion process, and that simply painting on an adhesive is not good enough, results will improve. If we do not allow the adhesive to penetrate the etched zone, our patients will suffer with sensitivity. Today’s chemistry, with its hydrophilic components, has the ability to penetrate and seal tubules.

Of course, not all adhesives perform equally well, but if used properly, clinicians should not have problems with sensitivity with any current adhesive systems. It should be understood that the best bonding is achieved by locking a strong adhesive into the etched surface.

For this reason, we advise against the use of desensitizers since they compete for the same space that the adhesive should be entering into and subsequently prove to lower bond strength a slight amount. To address durability, it is useful to consider what makes some of the adhesive systems work.

Early adhesives used primers to first make the etched surface ready to receive a very hydrophobic adhesive. These early adhesives proved the test of time when used properly. The hydrophobic polymer system was able to withstand years of use in the oral cavity with very little sign of water absorption.

This made it very stable, but the application was tedious, requiring more steps, and with extra steps often comes more mistakes. Adhesives that removed the primer step by adding more hydrophilic monomers to the adhesive were slowly, and very cautiously, adopted in the mid- to late-'90s. This type of chemistry was met with considerable skepticism, as it was felt that the polymers were at risk of hydrolyzation or breakdown in long-term exposure to water. Time has proven that many of these adhesives are working well with 20 years of service to draw on.

Speed and ease of use continue to drive the market, and thus the self-etch world emerged. Removing the separate phosphoric step, yet still etching with an acid monomer worked, but with greatly reduced effectiveness on enamel. The effectiveness was reduced so much that selective etching of enamel became a must to get the desired strength.

Related article: 4 big benefits of resin cements

The need for this step meant that the promise of speed was not really met. With the use of acidic monomers came a serious issue of hydrolytic breakdown. The early self-etch systems produced a rash of problems with short life spans, and even more so with later all-in-one products.

In the past 10 years, much has been done to address issues of durability, with some manufacturers using a balanced blend of hydrophobic and hydrophilic monomers. The most effective adhesives are able to penetrate the moist, etched tooth surfaces and then polymerize into durable surfaces, which are hydrophobic enough to resist water absorption for years to come.

By studying the research, one can easily find products that regularly rank high in bond strength, but we should also look for long-term bonding data. (Note that presently we have 8.5-year data on Peak®SE Primer and Universal Bond adhesive with no signs of bond strength degradation.)

Adhesives should be puddled onto the working surface (not starved) and rubbed/burnished or scrubbed into all areas of the etched dentin. With this technique, there is a much higher likelihood of complete penetration into every tubule. Enamel with less porosity than dentin does not need to be aggressively scrubbed but is optimally addressed with light agitation and painting. After application, the adhesive must be thinned to a stretched tight surface (similar to plastic wrap) with no pooling. This means every surface will have the ideal thickness for the ideal mechanics of adhesion to take place.

Light curing should be accomplished with a trusted light source. It is remarkably common for lights to be positioned improperly, especially on posterior teeth. The light should be able to be directed perpendicular to the working surface. This is particularly problematic in deep Class II restorations where matrix bands and cusps often obstruct lights built with the traditional 45-degree angle fiber optic or head. Many lights just don’t have a large enough area or footprint to ensure that you are getting the light where you want it.

Finally, the light should be held as close as possible so that as much energy as possible is able to reach the adhesive/composite as is reasonably possible. Fast curing is usually not as good as slower curing, primarily because it is too easy to wander off point, if only for a second, and we risk a significant amount of the intended energy. With this information, we should be able to rely on our adhesives as never before.

Many clinicians find that with proper techniques and good material, the majority of adhesively bonded restorations last well beyond 15 years with few signs of degradation. This is much longer than the five to seven years commonly cited in the literature. Bonding to tooth structure shouldn’t be a mystery and should bring opportunities never before provided in dentistry.